In learning the art of storytelling by animation, I have discovered that language has an anatomy. Every spoken word, whether uttered by a living person or by a cartoon character, has its facial grimace, emphasizing the meaning.

— Walt Disney

Chapter 6

The Drawing Board

"The tools used do not run the artist. It’s the artist that runs the tools."

Read More »

"When you witness a master visual storyteller at work, you can forget that you’re looking at a two dimensional line drawing…"

Read More »The "fine arts" are recognized as being produced more for beauty or spiritual significance than for physical utility. They are: Music, Literature, Painting, Sculpture, Theatre and Dance. Film has been officially called "the Seventh Art," as it can provide beauty and spiritual significance, as can comics and interactive games (play Tomb Raider II and see Venice).

In his book Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud delves into not just the creative process of the comic book, but truly the creative process in general. He defines the path of which any art form takes into six basic steps, 1) Idea/Purpose, or the inner passion for expressing one self creatively, 2) Form; that which the final product will take – comic book, animation or interactive game? 3) Idiom, or as he describes it; the genre for which the work belongs to — first-person shooter or graphic novel, 4) The structure of the production, the do's and do not's, 5) The chosen craft, with whatever required skills and then 6) the exposure of the work and the catalyst from which it will be revealed.

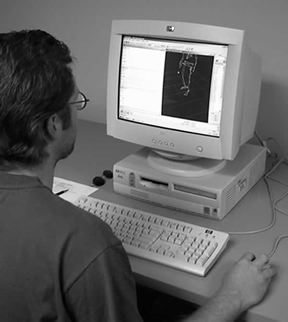

Today, many artists, illustrators in particular, who come up in the traditional media missed the tactile working with paper and paint and younger artists don't get that low-tech skill developed; a basic exercise for the creative muscles. Wayne Hanna, Academic Director of Visual Communications for the Illinois Institute of Art believes that that can be both a positive and a negative. "People that weren't exposed to that don't have that. The flip side is that I think artists that didn't experience that have a whole new set of values and fulfillments that are electronic, so it sort of expands their capabilities beyond the physical limitations of using a 1200 dpi pencil."

As Hanna mentioned early in this book, the power of technology should serve as a tool to the creative process and not become the creative process. Artists need to stretch beyond what they understand of the world and think outside the box, beyond even the software limitations, and make technology a servant, rather than the other way around. "One of the problems I see is after an artist masters the software, they limit their problem solving to what the software can accomplish, rather than looking at the problem, finding the best solution to the problem and then figuring out how to make software accomplish that for you. I call it "design by default."

Although educational institutions such as the Illinois Institute of Art has many technological courses, from digital filmmaking to 3-D modeling, but the core studies include the traditional fundamentals of art instruction; drawing, design and color theory, which are important to achieve a Bachelor of Fine Arts.

There is a need to develop skills beyond computer literacy, in order to achieve success as an artist in new media. "For example, the course path for a BFA in Media Arts and Animation requires courses such as fundamentals in design, English I, life drawing, color theory, effective speaking and even physics," said Hanna. "An artist who's required to design and illustrate computer 3-D animation needs to understand far more than how to draw dinosaurs—they need to be able to problem solve in that environment." Today's students are being prepared for a new visual literacy; for a creative world that cross-pollinates art and science to create a new attainment, a new level of three-dimensional consciousness.

The realistic figures seen in animation, storyboards and comics are drawn, sometimes using reference and sometimes from the artist's imagination. This is a skill that requires a synchronicity of knowledge and talent; a balance of both hemispheres of the brain. In order to be successful at dynamic imagery, the artist's brain needs to be "programmed" with enough data to be able to draw a wide variety of objects and figures in numerous poses; visual problem solving.

The success of visual storytelling also relies on the artist's [auteur] ability to create an environment that is real and immersive. However, each visual media has various layers of immersive powers based on the imagery presented. For example, in a comic book, an artist can draw a man dressed in skin-tight leotards swinging from building to building from a web that he shoots out of a invisible cartridge and become immersed in the fantasy as real, because there are elements of reality to support the illusion; buildings, people, cars, newspapers—all of which set a backdrop of reality. This is more easily accomplished in film, again because of the photographic visuals. In between is the 3-D rendering of games, which is a cross between to wildly bizarre (from a reality perspective), which only the talent of an artist could succeed in presenting, to the confines of the photographic reality of film. There are fantastic images and characters that can be presented on film and that blend into the environment, conceived as part of the photographic world on the screen. Most of these elements are recognized and categorized within the human psyche to bring forth that immersive level of reality. For example, the dinosaurs of the film of Jurassic Park looked more real than the dinosaurs of the animated film Dinosaur. The dinosaurs in Jurassic Park were set within the environment of a photographic reality and portrayed as part of the animal kingdom. While in the film Dinosaur, even though the environment was rendered to be as realistic as possible, the illusion of reality wasn't as strong (beside the fact that they talked). The point is that a film like Dinosaur or even Shrek doesn't have to be as photographically precise as a live action film to be immersive, just as a comic book doesn't need to be; it's the art itself that contributes to the visual experience.

If a movie such as Final Fantasy establishes itself as "photographic" in the minds of the audience (through photographic-like marketing), the audience will have that expectation, so; the slightest flaw in the representation of a walk or movement would interrupt that immersive experience. This is why motion capture technology is used in most 3-D animation and modeling. The motion capture process "traces" or "copies" the movements of real-life for more naturalistic looking characters. It's the same thing as the comic book artist using photographic reference, only with 3-D animation; they're using a living and breathing reference.

There will come a time when there won't be any difference between film and animation, but as Scott McCloud points out; the simplicity of the animated or cartoon image is universally recognized. Once those images are given structure and detail, they begin to lose the "interpersonal" acceptance of the characters. It becomes passive, laid back and linear. This is where the interactive element may compensate for the loss of the original mental and emotional participation.

"I have a little rule in my head — never compromise a story just because it will be hard to draw."

—Jeff Smith

Although, film, interactive games and comic books are very different products, the advent of more powerful and sophisticated computer graphics technology brings the artist's imaginative expression to life in any media. Films have become more "comic bookie" and an interactive game, where the imagery is fully rendered, becomes the stage for moving comic book-like worlds and characters. This becomes a natural extension of the artist's own imagination, rather than a photographic representation. And again, as films become more and more rendered, the same rules that have applied to comics and interactive games will become more prominent.

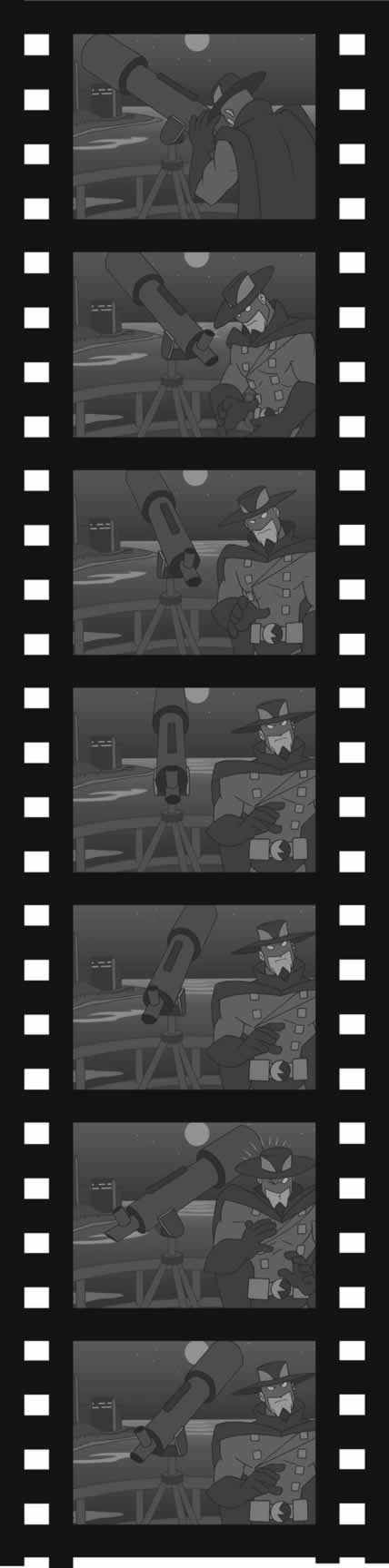

All visual communications start from the drawing board. Here are a few conceptual to animation cell stages for Age of the Guardian Strangers.

Copyright: Age of the Guardian Strangers, is TM & © 2001 BOXTOPTV.COM. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

In whatever medium a storyteller is working in, from film, comics to interactive games, the best way to produce the best work is to draw from life and reference. Much of the knowledge gained from drawing imagery, stories and characters form real life will be in the form of symbols or ciphers the brain has been programmed with to represent the subjects previously drawn or articulated in whatever medium chosen.

Most people's drawing ability stops progressing after about age nine or ten, when society shifts the educational requirements in elementary school from a creative to more logical perquisite for higher education and left-brain dominance – so most adults draw like 5th graders. Our educational system does a fine job teaching and nurturing the left-brain, which is the logical, calculating hemisphere (where words and numbers come from), but the right-brain has been woefully uneducated for most of the last century, while the world literally exploded with visual media. The majority of human beings are only educating "half" of our brains. The students of art recognize and choose to unlock powerful forces of creative thinking, problem solving, insight, and the wonderful manifestation of visual literacy, or being able to draw from the mind's eye.

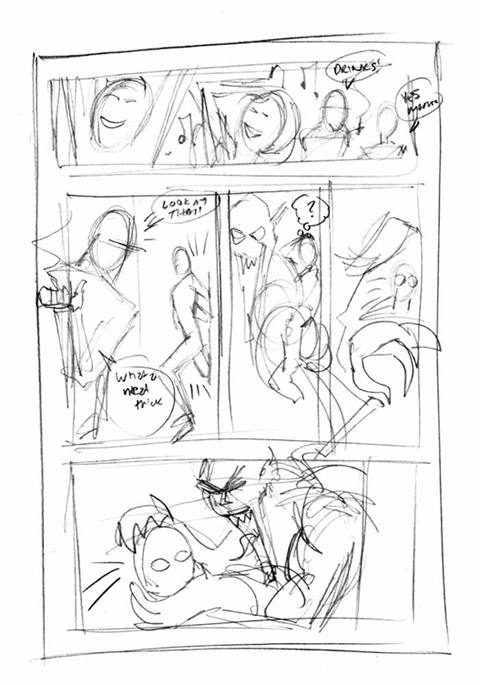

Here' the remarkably similar process in the production of comics —the same elements are used in each visual communication media, all of which use the most dynamic imagery to tell the story, or the "extremes." The real difference is in the amount of information projected within each "frame."

Copyright: Vesper's TM & © 2001 Anthony C. Caputo. All rights reserved.

Mark Manyen of Wounded Badger Interactive believes that "games are very art-centric." What he means is that in movies or even comics, to set up a shot of a rock—the entire rock isn't required. It can be half a rock – the side that's visible to the camera. It doesn't need any special texture, because the audience won't get any closer than the scene calls for; if the shot is set-up right, there's no need to worry about too much. On the other hand, it's very different in the interactive game environment, since the player can literally go anywhere in the 3D world in real-time; everything has got to be there and everything has got to be good. It's not just filming one side of the rock; there needs to be a virtual solid rock — top, bottom and sides. That's the interesting thing about being in the art in 3D games now – everything is important.

Technology has not only infiltrated the pre-production process, lettering and coloring for comics, but Corel Paint offers more flexibility with hard black lines, so you can ink on the computer. The Soul Chaser Betty comic book pages in Chapter 3 were inked using Corel paint.

Copyright: Soul Chaser Betty is TM & © 2001 Twilight Tangents. All rights reserved.

This chapter includes basic instruction in figure drawing and art. There are books that are recommended at the end of this book, to extend learning beyond these fundamentals, which begins with the ability to draw at a level of sophistication that illustrates the world around us in a realistic representation. An entry level art student is not expected to produce Shakespearean prose just because he/she knows how to read. This is a start.

The ability to draw is the number one requirement that is still requested by prospective employees, says Wayne Hanna, "The tools used do not run the artist. It's the artist that runs the tools."

After 5th grade, the ciphers of reality in the human brain stop progressing art sophistication, because the programming in their heads stops upgrading the data. This frustration is usually caused by the strong unfulfilled desire to be able to draw "realistically." Most people don't naturally know how to observe and draw "realistically" from life, so they get frustrated and give up and become awed by those who can as if it were magic. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the innovators of the visual arts can see what no one else can see and create what no one else could envision. This core competency is the cornerstone of artistic expression.

A good visual storytelling artist has to draw everything on and off this planet with a convincing level of skill, whether for final production or to communicate a visual foundation for dynamic media. Other fine and commercial artists end up specializing in one or two subjects (such as head portraits, flowers, product shots, and so on). However, a comic's artist has to draw a variety of figure types, city scenes, cars, animals, fantasy creatures, and so on – all with an equal level of ability and realism. They have developed their skill beyond traditional artists and this provides a canvas for dramatic imagery. If an artist draws people well, but his/her horses look very weak, the difference in drawing levels will make the weaker drawing stand out that much more and will distract the audience from the flow of the story (hence the face of The Rock on a computer generated scorpion monster in Mummy Returns).

A good visual storytelling artist has to draw everything on and off this planet with a convincing level of skill, whether for final production or to communicate a visual foundation for dynamic media. This includes outlandish characters, craters, people, cars, trees and buildings.

Copyright: Vesper's TM & © 2001 Anthony C. Caputo. All rights reserved.

Additionally, a good artist has to know what constitutes solid visual storytelling in order to thrive in visual media. Unfortunately, most people couldn't tell what's good visual storytelling; only bad visual storytelling. That's what Part II of this book is about –better visual storytelling—in whatever medium.

Just as traditional artists use the wooden art manikin, 3-D animators use "living reference," by building upon a wired manikin by way of Motion Capture technology provides a means of "tracing" life-like movements.

Copyright: Photos courtesy Red Eye Studios

The final product of most comics art is rendered in line, while in film and interactive games, it may start with being rendered in line (or polygons), but the finished product moves into something perceived as even more realistic – photographic or 3-D rendering. Therefore, when drawing comic books, the lines must represent for more realism than for storyboards; the less detail and lines in the art make those fewer lines even more important and powerful. Andrew Loomis, artist and author of Figure Drawing for All It's Worth says, "The eye perceives form much more readily by contour or edge than by…modeling. Yet there is really no outline on form; rather, there is a silhouette of contour, encompassing as much of the form as we can see from a single viewpoint. We must out of necessity limit the form in some way. So we draw a line – an outline."

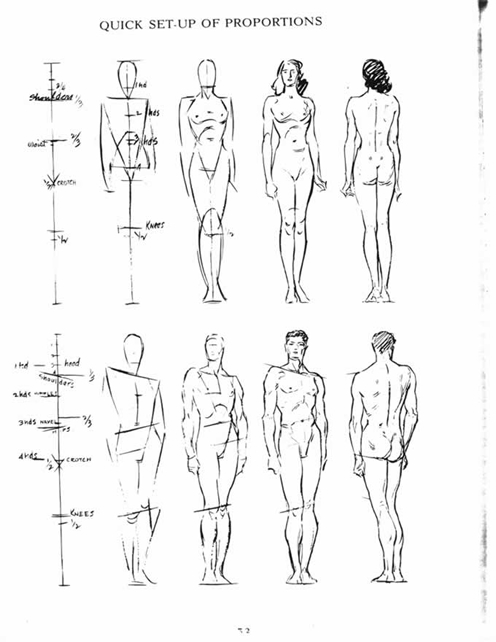

Andrew Loomis was a paramount illustrator of the 1930s and 1940s and is best known for the first art instructional book on dynamic anatomy and fashion illustration that presented the world with the human proportional chart in Figure XX. This book was first published in 1943, and although the many styles and tools of drawing may have changed since then, this framework still holds true to this day and is revered by all who recognize this important contribution to the world of art.

Line is also used to render forms within the outline of the figure – representing shading on forms from lighting. As Chapter 1 points out about our ancient ancestors, this is nothing new; the human mind converts two-dimensional imagery into line to decipher its meaning.

Line can also be used in a decorative way. Often, to the non-artist, the art that looks like it has the simplest or least line work looks less impressive than art that is highly rendered with lots of lines. However, the lower the number of lines an artist puts down, the more important each line becomes. This is because much more information has to be transmitted to the viewer through a line when there are fewer of them. Artists like Wally Wood are masters of this skill, but a lesser artist can make a passable drawing of a cheekbone by cross hatching the area – even if the artist isn't exactly sure of the underlying bone and muscle structure. The skilled minimalist can convey the structure in one or two perfectly placed lines.

The artist who has mastered the line can say more with less.

Copyright: Patrick the Wolf Boy is TM & © 2001 Arthur Baltazar & Franco Aureliani. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Lines can be thick, thin, mechanical, loose – anything. There is an almost limitless variety to line. Artists in training should try to sketch using a wide variety of lines to gain familiarity and confidence with a variety of approaches.

A comic's artist has the ability to render realism, without any high technology devices – just the low-tech pencil. Artists have to learn to use a delicate blend of reference, from film, pictures, photographs and even models, and the artist's imagination. This includes being able to draw anything on or off this world!

While commercial of fine artists are satisfied concentrating on one or two areas or subjects, such as portraits, landscapes, cars or animals; the comic artist (overachievers) have to do research, where necessary, and draw everything in the course of the story at the same level of believability. Even a small unbelievable element in the artwork may throw the reader out of the flow of the story. An example of this is drawing realistic people within an environment of poorly drawn inanimate objects. If a story calls for a close-up of a person getting bad news on the phone, traditionally, the phone handsets, with their dynamic angles and smooth surface, can be quite difficult to draw in outline form. If the face is rendered convincingly but the person is holding an unconvincing blob for a phone, the realism is destroyed. Or, if the artist "cheats" by pulling way back and/or silhouetting the shot, the desired dramatic effect is lost.

Whatever an artist doesn't like to draw is what they've been neglecting to draw and therefore need to work on the most to heighten their level of skills. The most common items that most comic artists dislike, due to complexity are cars, which, much like the phone handset, includes dynamic angles, a smooth surface, but also three-dimensional details and glass. There are also buildings, which require a mastery of perspective drawing and architectural knowledge, second only to a real architect. Then there are the animals, with the enormous varieties of physical anatomies and features. Often, if an artist forces his/herself to conquer a drawing deficiency, that subject becomes one of the artist's favorite things to illustrate.

Drawing Basics

While this book is not meant to be the definitive "how to draw" work, it‘s necessary to briefly go into some basic drawing topics and how they relate to visual storytelling.

The Head

The head and face are important for presenting realism. It's one of the most important elements in creating the "point of reference" needed to guide the reader clearly along in any sequential art form, from film to comic books. It would be rather confusing if in each scene (or panel) the characters within that scene appeared different.

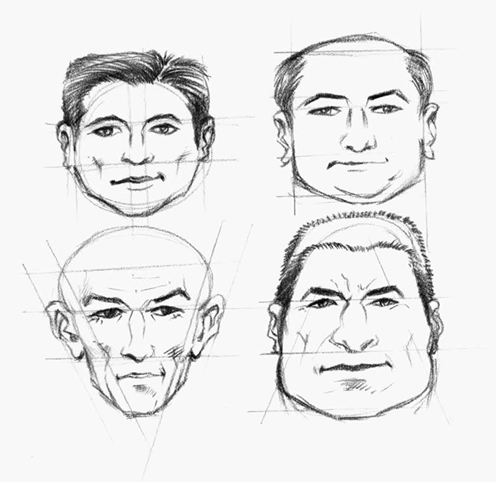

There are many art instruction books available on the subject of heads, but here is the basic egg structure, with the face being divided up into thirds; one third the forehead, one-third the nose, and one third the from the bottom of the nose to the chin. Following these proportions will provide a guide at any angle.

The head is usually divided into thirds, and by giving the head a specific shape, it helps to continue the resemblance of that character throughout the frames.

Figure drawing and anatomy is important for comic book artists, due to the fact that they're working on a final product, not the visual foundation of a final product in film or 3D. The complexity of the world they create needs to be realistic, and they must be able to draw all types of people convincingly. This is to create that realism necessary to give the unreal vitality. Most of our lead characters have idealistic proportions and features - rendered in an approach called "heroic representationalism" (for lack of a better shorter term). However, these characters interact with people in a wide range of body sizes, types, and ages. So, it‘s necessary to draw all sorts of people with the same high level of accuracy.

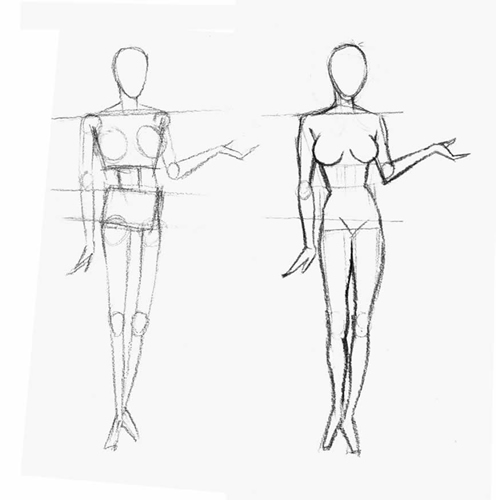

Every figure should be built from some kind of skeletal structure or "manikin," which provides a framework for drawing accurate anatomy and proportions. See the Andrew Loomis section.

Body dynamics and angles are usually exaggerated to add dramatics. The natural counterbalance the masses that a figure in motion exhibits can aid drawing dynamically, such as the tilt of the shoulders often balanced by an opposite tilt of the hips.

It's best not to get too caught up in anatomical details, early on in studies. Learn the major "masses" and "planes" of the body and head first before wondering if all the striations of the deltoid muscles are right. Learn the position, mass, planes, origins and insertions of the major muscle groups and will then have enough knowledge to be able to draw, and exaggerate where needed, in a convincing manner. There are a number of recommended books on anatomy listed in the appendix of this book.

The heroic male and female are taller and more solid looking than a more realistically drawn figure. The male is broader, more massive and muscular than his realistic counterpart. The female, though still feminine, has a much broader look at the shoulders. Making sure to differentiate between the normal and heroic figures is very important.

"These proportions have been worked out with a great deal of effort and, as far as I know, have never been put down for the artist. The scale assumes that the child will grow to be an ideal adult of eight head units. If, for instance, you want to draw a man or a woman (about half a head shorter than you would draw the man) with a five-year-old boy, you have here his relative height. Children less than ten years old are made a little shorter and chubbier than normal, since this effect is considered more desirable; those over ten, a little taller than normal — for the same reason."

Copyright: From FIGURE DRAWING FOR ALL ITS WORTH by Andrew Loomis, © 1943 by Andrew Loomis, renewed 1971 by Ethel Loomis. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Putman, Inc.

Kerry Gammill was once asked why artists draw their human figures as these perfect specimens. "Because we can," was his reply. The same obsession with the human form was also the internal force that drove Michelangelo to paint the perfect naked images on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is the same reason why comic artists draw in heroic representationalism. The example of the "normal" human figure in Figure 6.20, is why comic book artist's, with their heighten skills, expound on the academic version of the human image, just as they push the boundaries of reality in the stories they create. It's because they can, just as Hollywood, with the use of beautiful people and computer graphics can improve and enhance anything that the artists involved in the picture can ever imagine. Most fashion illustrators have stretched the figure even beyond eight heads (see Figure 6.20). The control of the appearance and height of the figure is largely controlled by the size of the head.

Andrew Loomis was a popular fashion artist in the 1930s and 1940s and also authored a number of highly detailed books on drawing the human figure. All of those books are currently out of print. Penguin owns Viking Press, which was the original publisher of these works. The book Figure Drawing for All It's Worth is a fantastic study of the human figure and is highly recommended by the likes of Neal Adams, John Byrne and Walt Simonson. Loomis was the first artist to publish the proportional charts all illustrators, from comics to fashion designers to storyboards to interactive games, use today.

Copyright: From FIGURE DRAWING FOR ALL ITS WORTH by Andrew Loomis, © 1943 by Andrew Loomis, renewed 1971 by Ethel Loomis. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Putman, Inc.

Once more from Loomis' book, here is a reproduction of the great mannequin frame that's used as the skeleton to build up his figures, although, many artists have their own version of the manikin. This is a good place to start when developing your own means of building the human frame.

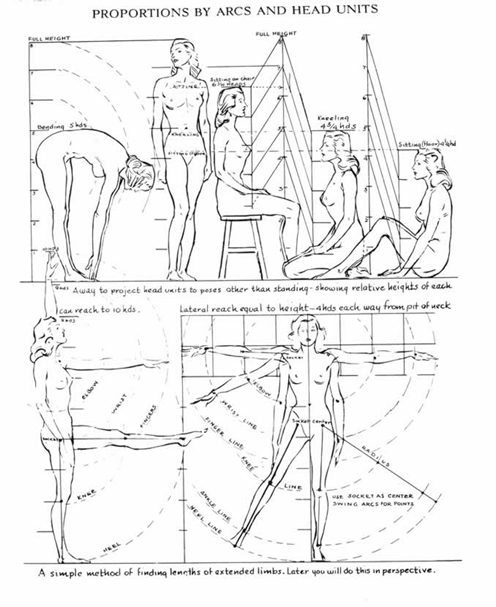

"Many artists have difficulty in placing figures in their picture and properly relating them to each other, especially if the complete figure is not shown. The solution is to draw a key figure for standing or sitting poses. Either the whole figure or any part of it can then be scaled with the horizon. AB is taken as the head measurement and applied to all standing figures; CD to the sitting figures. This applies when all figures are on the same ground plane. You can place a point anywhere within your space and find the relative size of the figure or portion of the figure at precisely that spot. Obviously everything else should be drawn to the same horizon and scaled so that the figures are relative. For instance, draw a key horse or cow or chair or boat. The important thing is that all figures retain their size relationships, no matter how close or distant. A picture can have only one horizon moves up or down with the observer. It is not possible to look over the horizon, for it is constituted by the eye level or lens level of the subject. The horizon on an open, flat plane of land or water is visible. Among hills or indoors it may not be actually visible, but your eye level determines it. If you do not understand perspective, there is a good book on the subject, Perspective Made Easy, available at most booksellers."

A good anatomy book is recommended and a few are suggested in the appendix of this book. Gray's Anatomy is a great reference manual if a med-student, but it is basically worthless for an artist.

Never underestimate the importance of using reference, from photos, real-life and other media. If an artist doesn't know what something looks like, they can't draw it, and if they try; the [less forgiving] audience will then know that they can't draw it. There is a significant difference is how different objects actually look, when casually glancing at them, as compared to observing them as an artist. By using reference on a variety of buildings, they will always look more believable than trying to invent them out of the artist's imagination.

Also, remember that referencing something doesn't mean a photo on a light box and trace it. While this is fine to do from time to time (and is used quite often with motion capture techniques in interactive games), and helps in learning object form, it tends to look static and lack intuitive life. It's always better to reference something and draw it by hand. This way, the artist add their own dynamics to the image, rather than sticking to the static reality of a photograph

It is recommended to work on increasing stylistic versatility, because doing this will increase the artistic rendering repertoire. Sit down once a week and draw an object in at least 4 totally different styles. The object can be anything - a figure, part of a figure, a house, car, tree, etc. Some example styles would be: high contrast, leading edge contour, dry brush, ink wash, stipple, etc., whatever styles come to mind. By drawing the same object in several different styles it forces a multi-dimensional view of the object and will help break out of any stylistic ruts and will increase drawing knowledge.